The Göttingen Septuagint is the Cadillac of Septuagint editions. It’s the largest scholarly edition of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Its full name is Septuaginta: Vetus Testamentum Graecum Auctoritate Academiae Scientiarum Gottingensis editum, published by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen, Germany. The Göttingen Septuagint has published more than 20 volumes spanning some 40 biblical books (counting the minor prophets as 12), and publication of additional volumes is in progress.

But the Göttingen Septuagint is not for the faint of heart, or for the reader who is unwilling to put some serious work in to understanding the layout and import of the edition and its critical apparatuses. A challenge to using Göttingen is the paucity of material available about the project, even in books about the Septuagint. An additional challenge is that the critical apparatuses contain Greek, abbreviated Greek, and abbreviated Latin. The introductions to each volume are in German, though below I cite from English translations of the introductions to the volumes of the Pentateuch.

It is my intention with this post, and a second to follow, to give a short primer or user’s guide to the Göttingen edition. Here I offer suggestions on how to read and understand the text, the apparatuses, the sigla/abbreviations, the introductions, and point to additional resources that will be of benefit to the Göttingen user.

I recently put together a basic orientation to the scholarly editions of the Hebrew Bible and the Greek translation of the same. That is here. It is worth nothing again that the International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies (IOSCS) has a good, succinct article on the various editions of the Septuagint. Below, “OG” stands for “Old Greek.” They write:

The creation and propagation of a critical text of the LXX/OG has been a basic concern in modern scholarship. The two great text editions begun in the early 20th century are the Cambridge Septuagint and the Göttingen Septuagint, each with a “minor edition” (editio minor) and a “major edition” (editio maior). For Cambridge this means respectively H. B. Swete, The Old Testament in Greek (1909-1922) and the so-called “Larger Cambridge Septuagint” by A. E. Brooke, N. McLean, (and H. St. John Thackeray) (1906-). For Göttingen it denotes respectively Alfred Rahlfs’s Handausgabe (1935) and the “Larger Göttingen Septuagint” (1931-). Though Rahlfs (editio minor) can be called a semi-critical edition, the Göttingen Septuaginta (editio maior) presents a fully critical text….

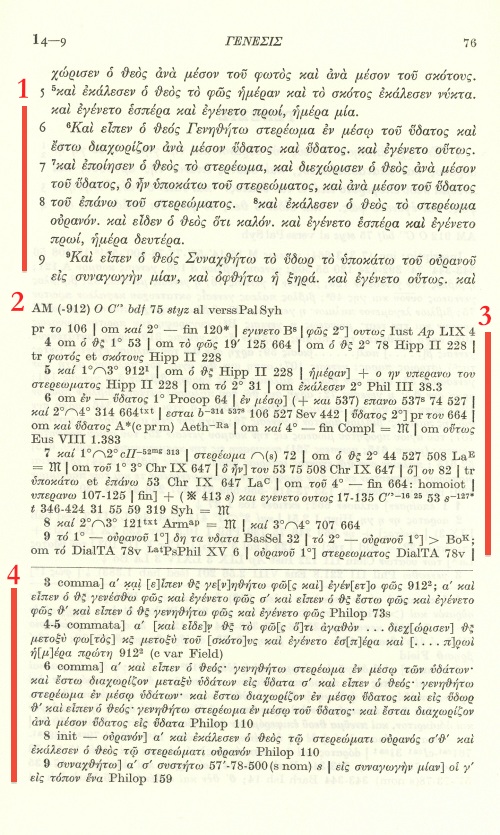

In other words, rather than using a text based on an actual manuscript (as BHS, based on the Leningrad Codex, does), Göttingen utilizes a reconstructed text informed by a thorough examination of manuscript evidence. Göttingen has two critical apparatuses at the bottom of the page of most volumes. Because it is an editio maior and not an editio minor like Rahlfs, a given print page can have just a few lines of actual biblical text, with the rest being taken up by the apparatuses. Here’s a sample page from Genesis 1. Note the #s 1-4 that I’ve added to highlight the different parts of a page. Below I explain #1 and #2; the rest comes in a follow up post.

1. The reconstructed Greek critical text (“Der kritische Text”)

With verse references in both the margin and in the body of the text, the top portion of each page of the Göttingen Septuagint is the editorially reconstructed text of each biblical book. In the page from Genesis 1 above, you’ll notice that the text includes punctuation, accents, and breathing marks.

Like the NA27 (and now NA28) and UBS4 versions of the Greek New Testament, Göttingen is a critical or “eclectic” edition, which “may be described as a collection of the oldest recoverable texts, carefully restored book by book (or section by section), aiming at achieving the closest approximation to the original translations (from Hebrew or Aramaic) or compositions (in Greek), systematically reconstructed from the widest array of relevant textual data (including controlled conjecture)” (IOSCS, “Critical Editions”).

Of the critical text, John William Wevers, in his introduction to Genesis in Göttingen, writes:

Since it must be presupposed that this text will be standard for a long time, the stance taken by the editor over against the critical text was intentionally conservative. In general conjectures were avoided, even though it might be expected that future recognition would possibly confirm such conjectures.

It must be clearly evident that the critical text here offered labored under certain limitations. The mss, versions and patristic witnesses which are available to us bring us with few and small exceptions no further back than the second century of our era. Although we do know on the basis of second and third century B.C.E. papyri something about the character of every day Greek used, our knowledge of contemporary literary Greek is very limited indeed. In other words, the critical text here offered is an approximation of the original LXX text, hopefully the best which could be reconstructed on the basis of the present level of our knowledge. The editor entertains no illusion that he has restored throughout the original text of the LXX.

One cannot simply say, “The LXX says…,” because then inevitably an appropriate response is, “Which LXX? Which manuscript? Which or whose best attempt at reconstruction?” So “approximation of the original” and “hopefully the best which could be reconstructed” are key phrases here.

All the same, especially in the newer Göttingen editions, the volume editors have viewed and listed the readings of many manuscripts and versions. The critical apparatuses are where they list those readings, so the user of Göttingen can see other readings as they compare with the critically reconstructed text. (Because the Göttingen editions are critical/eclectic texts, no single manuscript will match the text of the Göttingen Septuagint.) And although scholarly editions of the Greek New Testament also present an eclectic text, neither the NA27 nor UBS 4 is an editio maior, as Göttingen is. (The Editio Critica Maior is just recently begun for the GNT.) Serious works in Septuagint studies, then, most often use the Göttingen text, where available, as a base.

2. The Source List (“Kopfleiste”)

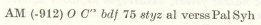

Not every volume has this feature, but the five Pentateuch volumes, Ruth, Esther, and others do. The Kopfleiste comes just below the text and above the apparatuses. Wevers notes it as a list of all manuscripts and versions used, listed in the order that they appear in the apparatus on that page. A fragmentary textual witness is enclosed in parenthesis.

In the above Kopfleiste, the parentheses around 912 mean that papyrus 912 is fragmentary. The “-” preceding it, Wevers notes, means that its text ends on the page in question. So although this particular Göttingen page has Genesis 1:4-9 reconstructed in the critical text (“Der kritische Text”), “(-912)” in the Kopfleiste indicates that the fragmentary papyrus 912 does not actually contain text for all the verses on the page. Looking up papyrus 912 in Wevers’s introduction to Genesis, in fact, confirms that this third to fourth century papyrus contains only Genesis 1:1-5.

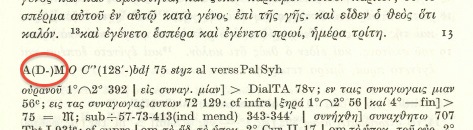

By contrast, the “(D-)” here

indicates that the uncial manuscript D has its text beginning on the page in which it appears in Göttingen. The above shot is from the Göttingen page containing Genesis 1:9-13. The first time D has anything to offer (since it is fragmentary, indicated by its enclosure in parentheses) is at 1:13. This alerts the reader that D has no witness to Genesis 1:1-12. Wevers’s introduction then gives more information about the contents of that manuscript. So, too, with the minuscule manuscript 128 above–the introduction says of 128, “Init [=Latin initium=the beginning] – 1,10 is absent.”

Wevers adds:

Should a piece of text be lacking due to some external circumstance in a particular ms, this is noted in the Source-List. For example if ms 17 lacks the text this is shown as O-17. What this means is that the entire O except 17 (which belongs to O) has the text in question. The abbreviation al (for alia manuscripta) refers to the mss which belong to no particular group, i.e. the so-called codices mixti as well as mss which are too fragmentary to allow classification. The expression verss designates all the versions which have the complete text of Genesis. Versions such as Syh to (31,53) and Pal, whose texts are not complete, are listed at the end of the Source-List (Kopfleiste).

In terms of the order of citing Greek textual witnesses:

In the apparatus the citation of Greek sources appears in the following order: First place is occupied by the uncial texts in alphabetical order, and characterized by a capital letter. Then the papyri are cited in the order of 801 to 999. Then the hexaplaric group [AKJ: “O” above] is given as well as the Catena groups [AKJ: C‘’], with the mss groups following in order as: b d f n s t y z; then the codd mixti, followed by the mss without a Rahlfs number. Next come the NT citations, and finally, the rest of the patristic witnesses in alphabetic order.

In the next part of this Göttingen Septuagint primer, I’ll explore #3 and #4 above, the First Critical Apparatus (“Apparat I”) and the Second Critical Apparatus (“Apparat II”), as well as take a closer look at the contents of the Introductions in the Göttingen editions (“Die Einleitung”).

UPDATE: Part 2 of the primer is here, with still more to follow.

Thanks to Brian Davidson of LXXI for his helpful suggestions on an earlier draft of this post.

Reblogged this on Streaming Along the Negeb.

Reblogged this on Rosary2007's Weblog and commented:

This is a v ery good help!